Last Sunday morning, Jawad Khaki, imam and co-founder of the IMAN Center of Kirkland, wrote an email to friends and supporters.

“Our condemnation and denouncement of the horrific mass killings in Lebanon, France, Nigeria, Bangladesh, U.S.A., Afghanistan and many other parts of the world cannot possibly express the pain and anguish of all upstanding citizens of the world,” he wrote in the note, which he also posted on Facebook.

Many Muslims and non-Muslims have been voicing similar sentiments. But Khaki, a 57-year-old entrepreneur and philanthropist who worked for 20 years at Microsoft, most recently as a vice president, did not stop there.

“Please join me in calling upon Ayatullah Khameni and other religious leaders of Iran to stop the practice of chanting slogans of death after each ritual prayer,” he went on. “Please join me in calling upon leaders of Saudi Arabia to stop support of religious radicals from that country.”

His cri de couer came hours before President Obama, in an address to the nation prompted by the Dec. 2 terrorist shootings in San Bernardino, Calif., both criticized sweeping anti-Islamic sentiments and called upon Muslims to confront, “without excuse,” the extremism that has spread within some of their communities.

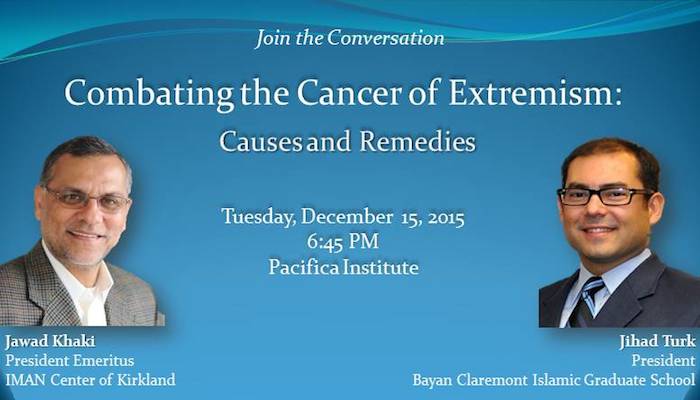

Khaki seems to be thinking along the same lines. On Tuesday, he will participate in an event titled “Combating the Cancer of Extremism.” Put on by the Pacifica Institute, a Turkish group promoting interfaith dialogue, it is being held in Bellevue and will feature Khaki, who belongs to the Shia branch of Islam, discussing the subject with a Sunni leader from California. The public is invited; an online RSVP is requested.

That leaders from Islam’s two main branches would come together is not insignificant, as Khaki noted during an interview last week. In his center’s light-filled sanctuary, covered with Middle Eastern rugs, the Tanzanian-born and British-educated Khaki discussed what he hopes to accomplish.

What follows is an edited version of the conversation.

Q: Let me start with this email you sent out …

A: I was thinking about it since Friday, and it was really bugging me.

When you look at Iran and Saudi Arabia, these are the two leading nations of Islam. And I’m saying the messages that we get are not messages that inspire people. So we’ve got to change that. We’ve got to stop the support for radicalism that comes from the weird ideologies that come from Saudi Arabia. At the same time, I’ve been to Iran. It really bothers me that after each prayer, they say: “Death to America. Death to Israel. Death to Britain.”

After prayer, they should be saying: “Long live humanity.” Or, “Death to poverty, death to illiteracy, death to evils in society.”

A: Was [your email] related to San Bernardino?

Q: Look, when an event like this happens, we want to make sure the messages that come out there do not cause people to do crazy things. I don’t know what motivated this guy to get radical. And I need to reject that. I have to categorically reject indiscriminate slogans of death. I don’t need to be a Muslim or a Jew or a Christian to do that. I have to be a human being to do that.

Q: Do you feel, as a Muslim, you have a special responsibility?

A: Absolutely, because of the teaching in the Quran: When you kill an innocent individual, it’s as if you killed the entire humanity; when you save a person’s life, you saved the entire humanity.

On Sunday, I sent this email out. Later … Trump says this crazy thing about Muslims. [GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump called for a ban on Muslims entering the U.S.] So we’ve got a couple of struggles. We’ve got a struggle at home. And we’ve got a struggle overseas. We’re caught in the crossfire.

Q: Are you talking about trying to lobby our government to put pressure on Iran or Saudi Arabia?

A: We need to engage and get to the roots of the problem, not in a way to put pressure, to actually work together with Saudis. Let us sit down and figure out: Where is this hate ideology coming from? Is it the textbooks that you use in the school? Is it the teaching that you do in your madrassas?

The whole entire world agrees that we’ve got a problem with radical Islam. So let us identify the roots of radicalism in each of these countries and try to do something about it.

Q: We talked about Saudi Arabia. We talked about Iran. What about here?

A: I’ve been fortunate, I’ve had opportunity to interact with very diverse groups of people, in many different settings, whether it be in work settings or neighborhood settings, where I take my kids to play baseball, basketball, soccer, or in school PTA meetings or community forums, in churches, in synagogues, in town halls. And that access was possible for me because of my work and the education I’ve got.

Many of the people who come to this country, they might not all have these opportunities. And we need to create these opportunities.

We need to figure out how we can facilitate the assimilation of these communities in our society.

Q: Do you feel like some mosques may be apart from the larger American society?

A: I’m not aware of any problems in America. I might be aware in England, in Europe. What I’m saying: Are we doing enough?

Q: What would you like to see them do?

A: Serve their local neighbor. Staff soup kitchens. Fight homelessness. Fight drug abuse. Provide education. Help people succeed in colleges.

Q: You are participating in this dialogue next Tuesday, which I understand was partly your idea.

A: Tezcan [Inanlar, regional director of the Pacifica Institute] and I talk about this stuff. We do believe we need to combat extremism and all this violent stuff. And we need to raise awareness, both in the Muslim community and the broader community. I don’t make a distinction. Who is my community? My community is everybody.

After 9/11, one thing that really impressed me a lot was to see the maturity … and the self-confidence of the Jewish community and the Christian community and even atheists … [who] wanted to engage and understand Muslims.

It was not the response that I see today from people like Donald Trump.

Q: You feel like after 9/11, people were more inclusive than now?

A: Temple B’nai Torah said: Jawad, come here, let us learn more about Islam. St. Thomas Episcopal Church. Northwest Unitarian Church. So many Presbyterian churches, Methodist, all these places, they invited me.

This is really another thing I would say about the Muslim community here. We have a lesson to learn from the non-Muslim community. When things that did not make sense happened, the reaction from the non-Muslim community was to reach out and understand. Whereas today, we have a hard time to facilitate a discussion between Muslim communities in the local area.

We have a hard time having two Muslim communities, two congregations, coming together.

Q: Why?

A: There is polarization around ideologies with the Shia/Sunni thing. Or there is polarization around personalities.

Q: What do you hope to accomplish next Tuesday?

A: We ought to be able to have an honest conversation between Muslims about what we need to do. I’m not sure we can identify what we need to do. But at least we can talk about it.

The ability to have conversation about topics that are sensitive — if we can do that in public, without really getting on the defensive, without really feeling pressure, I think it will be a big step.

Published on Seattle Times, 12 December 2015, Saturday

Related

- Gülen urges Muslims to denounce terrorism, promote human rights, education

- Dialogue Society Report on Violent Extremism

- Muslims Must Combat the Extremist Cancer

- Hizmet’s core teachings to undermine and negate extremism

- Fethullah Gülen’s specific responses against particular incidents of violent extremism

- The Gulen Movement: An Islamic Response to Terror as a Global Challenge

- The Gulen Movement: An Islamic Response to Terror as a Global Challenge (2)

- Islam and Terror: The Perspective of Fethullah Gülen

- Fethullah Gulen on "Islam and Terrorism"

- The Work of Fethullah Gulen and the Role of Non-violence in a Time of Terror (1)

- The Work of Fethullah Gulen and the Role of Non-violence in a Time of Terror (2)