People who Have Devoted Their Lives to Peace

Peace has many sides, and peacemakers are not all of one type. What peacemakers have in common is their willingness to put into action the thirst that all good people have for peace: to put their desire for peace into words, and to match their words with deeds. Peacemakers are those who are ready to work for change in society in non-violent ways, who protest injustice without acting unjustly toward those who perpetrate wrongs, who try to reconcile those involved in conflict without themselves becoming part of the conflict.

Peacemakers take risks. They risk losing the life of tranquillity, comfort, and complacency that is often mistaken for peace. They risk losing the esteem of family and friends by taking on unpopular causes and by associating with unwelcome people. They risk their freedom of movement, of speech, of association, especially when their efforts at peace bring them into confrontation with governments and powerful forces in society. They risk their very lives when their message of peace is an obstacle to the plans of the violent.

For religious believers, our faith shapes the way we understand peace. As a Christian, I find the teaching and example of Jesus compelling. “Peace I leave with you,” he said, “My peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.” Even though our inspiration for peacemaking is formed by our respective religious faiths, honesty and human fellowship demands that we recognize that, just as all religions teach peace, so have all faiths produced outstanding examples of peacemakers.

It would be a good exercise for each of us to make a personal list of frontrunners for peace, simply in order to undertake the discipline of asking ourselves, “Who are my heroes of peace, and why?” In drawing up a list of peacemakers, we engage in a process of defining our own values and asking ourselves what peace means to us. In my short presentation, rather than repeating some of the great names like Gandhi, the Dalai Lama, Albert Einstein, and Pope John XXIII, I would like to mention four people - two Christians and two Muslims, who exemplify for me the spirit of peacemaking.

1. Rosa Parks: an ordinary person who brought about big changes.

The first person I want to mention is a woman from my native country, one whom I have never met but who has greatly influenced the direction of my life. This is Rosa Parks, an African-American, a Christian, member of the Baptist Church, who is still living and 90 years old this year. In 1955, I was 14 years old. To appreciate the achievement of Rosa Parks, you have to understand the racial situation in the United States at that time. In many places, African-Americans could not use the same restaurants, parks, or toilet facilities as other Americans. They could not send their children to the same schools, live in the same neighborhoods, or sit in the same seats in buses or trains.

Dramatic changes have taken place since then, and the catalyst for these changes was an ordinary 42-year-old woman who did not have the benefits of higher education or a position of power in society. Rosa Parks received her high school diploma by taking classes at night after working as a seamstress by day, sewing clothes at a large shop in Montgomery, Alabama. On 1 December 1955, when Rosa was returning home from work, seated in the first row of the “colored” section in the back of the bus, a white man got on. There were no more seats, so the bus driver asked Rosa and other African-Americans to move farther back so the man could sit down. The others moved, but Rosa stayed seated. The bus driver said, “I’ll have to arrest you,” she answered simply, “You may go on and do so, ” and Rosa Parks was arrested for her non-violent protest.

The young pastor of a Baptist parish in Montgomery heard about her arrest and organized a boycott of the bus company, and in this unassuming way the American civil rights movement started. The movement grew and came to include not only African-American but various sections of society. There were marches, demonstrations, letter-writing campaigns to politicians, sit-ins at bus stations, police headquarters, airports, and universities. Some of the civil rights activists were brutally killed, and usually the killers were not brought to justice.

In 1963, I was in the seminary studying theology. We weren’t much affected by the civil rights movement. My state had repealed its discriminatory laws, so the issue seemed distant from our daily lives. The movement was going on and we knew about it, but we weren’t really part of it.

Then in March, 1963, Martin Luther King, the young preacher who organized the bus boycott, called for a nationwide meeting to protest racial discrimination. Over 250,000 people gathered in Washington to hear him speak, and on that day Martin Luther King gave his famous, “I have a dream” speech. He said, “I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the children of former slaves and the children of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.” The civil rights movement, and Dr. King’s speech in particular, changed my life by offering me a new set of priorities and a sharpened commitment to social change.

I’ve learned several things from Rosa Parks. I learned that a peacemaker does not have to work from a position of political or economic power in society. A peacemaker need not belong to the dominant social, racial or ethnic majority. A peacemaker does not have to be equipped with the tools of formal higher education. A peacemaker who is convinced of the rightness of her or his cause and has the courage of his or her convictions can, by seizing the right moment and responding to it firmly and creatively, accomplish much. For me, Rosa Parks is evidence against the cynical commonplace that “The problem is too vast. There’s nothing we can do.”

2. Said Nursi: a Muslim thinker who advocated dialogue.

The next peacemaker I want to mention is Said Nursi. I do not think that I need to go into the details of his life, since many of you know much more about his life and thought than I do. Although I hope to focus mainly on Said Nursi’s ideas and actions as a peacemaker, it might be helpful to review a few basic facts of his life in order to situate his thought in its historical context.

Said Nursi was born in 1877 in the village of Nurs in the province of Bitlis in eastern Turkey. He studied the religious sciences in various medreses in Eastern Turkey, where he claims to have been influenced especially by the Islamic reformers such as Namik Kemal, Jamal al-Din Afghani and Muhammad Abduh. He became interested in politics and favored the views of Afghani concerning the unity or ittihad of the international Islamic community.

During the middle years of his life, Nursi’s thought underwent a radical change and he decided to devote his life to a study of the Qur’an in the light of modern sciences. His voluminous writings together form a comprehensive Qur’anic commentary called the Risale-i Nur (the Message of Light). Nursi’s basic intuition was the clash of world views represented by materialism, on the one hand, and by religious faith, on the other. He believed that the natural sciences, if divorced from a moral vision that could hold them together and give them direction, led inevitably to egoism, violence, and destructive behavior. It was the role of revealed truth to form people with a moral vision in which, as he states: “Conscience is illuminated by the religious sciences, and the mind is illuminated by the sciences of civilization. Wisdom occurs through the combination of these two.”

Nursi’s criticism of materialist tendencies in society and politics, and his opposition to Turkey’s engagement in wars and unholy alliances, caused him to be repeatedly put in prison or confined to house arrest. Although he lived in a period when Turkey was being torn apart by civil strife, revolution, war and a clash of world views, Nursi’s message was always of peace. The “Old Said” knew the ravages of war first hand, having taken part as a young man in the First World War, commanding militia forces in the Caucasus in defending his homeland against the Russian invasion. Even then, his religious commitment was foremost, and he dictated Qur’anic commentary to a scribe in the midst of battle. He was taken prisoner and transported to Russia as a prisoner-of-war, where he lived through the Russian revolution.

By the time of the Second World War, the “New Said” had undergone a spiritual pilgrimage, and the worldly events erupting around him hardly penetrated his awareness. He devoted his days and months in prison to the study of the Qur’an and, as he states, “In these last four years, I have known neither the stages of the war, nor its results, nor whether or not peace has been declared, and I have not asked, I have not knocked on the door of this sacred sura to learn how many allusions it contains to this century and its wars.” There is no doubt that Nursi’s transformation from activist to contemplative student of the Qur’an was influenced by the horrors of war that he had seen and experienced as a young man.

In his writings about peace, Nursi focuses on three aspects. Firstly, peace is the ultimate goal and reward of those who study and practice the Qur’anic teaching found in the Risale-i Nur. Secondly, peace is the serenity granted by God to faithful believers that enables them to bear hardship, injustice, and opposition with equanimity and forgiveness instead of seeking revenge. Thirdly, peace is a mission, a solemn duty, entrusted by God to the Islamic community. Muslims are to be peacemakers and builders of peace in this world. Nursi sees the task of Islamic civilization as one of striving for truth instead of force, establishing justice and harmony, attracting others by the power of love rather than by selfish ambition, strengthening the bonds of unity across religious, national and class lines rather than falling into divisive racist or nationalist attitudes (cf. The Damascus Sermon, p. 106.)

Said Nursi notes (The Flashes, Sixteenth Flash, p. 144) that he was often criticized because of his commitment to peace. At the time of the British and Italian invasions of Turkey, Nursi proposed prayers for peace and negotiated settlement and was consequently accused of indirectly supporting the aims of the aggressors. Nursi replied that he too wanted release, but not by using the same methods employed by the assailants. He stated that Islam teaches people to seek truth and uprightness, not to try to achieve their aims by use of force. He was asked whether freely relinquishing one’s rights for the sake of peace should not be considered a kind of compromise with wrongdoing. In response, he drew upon his experience in prison, stating: “A person who is in the right, is fair. He will sacrifice his dirhem’s worth of right for the general peace, which is worth a hundred.”

In his analysis of society in his day, Nursi considered that the dominant challenge to faith to be the secularist ideology promoted by the West. He felt that modern secularism had two faces. On the one hand, communism explicitly denied God’s existence and consciously fought against the place of religion in society. On the other, the modern capitalist systems, in their brand of secularism, did not deny God’s existence, but simply ignored the question of God and promoted a consumerist, materialist way of life, as if there were no God, or as though God had no moral will for humankind. In both types of secular society, some individuals might make a personal, private choice to follow a religious path, but religion should have nothing to say about politics, economics or the organization of society.

In response, Said Nursi held that in the situation of this modern world, religious believers face a similar struggle, that is, the challenge to lead a life of faith in which the purpose of human life is to worship God and to love others in obedience to God’s will, and to lead this life of faith in a world whose political, economic and social spheres are often dominated either by a militant atheism, such as that of communism, or by a practical atheism, where God is simply ignored, forgotten, or considered irrelevant.

Said Nursi does not advocate violence to oppose militant secularism. He says that the most important need today is for the greatest struggle, the jihad al-akbar of which the Qur’an speaks. This is the interior effort to bring every aspect of one’s life into submission to God’s will. This involves acknowledging and striving to overcome one’s own weaknesses and those of one’s nation. Too often, he says, believers are tempted to blame their problems on others when the real fault lies in themselves - the dishonesty, corruption, hypocrisy and favoritism that characterize many so-called “religious” societies.

He further advocates the struggle of speech, kalam, what might be called a critical dialogue aimed at convincing others of the need to submit one’s life to God’s will. Where Said Nursi is far ahead of his time is that he foresees that, in the struggle to carry on a critical dialogue with modern society, Muslims should not act alone but must work together with those he calls “true Christians,” in other words, Christians not in name only, but those who have interiorized the message which Christ brought, who practice their faith, and who are open and willing to cooperate with Muslims.

In contrast to the popular way in which many Muslims of his day looked at things, Said Nursi holds Muslims must not say that Christians are the enemy. Rather, Muslims and Christians have three common enemies that they have to face together: ignorance, poverty, dissension. In short, he sees the need for dialogue as arising from the challenges posed by secular society to Muslims and Christians and that dialogue should lead to a common stand favoring education, including ethical and spiritual formation to oppose the evil of ignorance, cooperation in development and welfare projects to oppose the evil of poverty, and efforts to unity and solidarity to oppose the enemy of dissension, factionalism, and polarization.

Said Nursi still hopes that before the end of time true Christianity will eventually be transformed into a form of Islam, but the differences that exist today between Islam and Christianity must not be considered obstacles to Muslim-Christian cooperation in facing the challenges of modern life. In fact, near the end of his life, in 1953, Said Nursi paid a visit in Istanbul to the Ecumenical Patriarch of the Orthodox Church to encourage Muslim-Christian dialogue. A few years earlier, in 1951, he sent a collection of his writings to Pope Pius XII, who acknowledged the gift with a handwritten note.

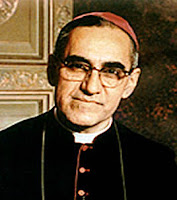

3. Oscar Romero: a peaceful defender of the poor.

My third example is a Christian, the former Catholic Archbishop of San Salvador in Central America. To those acquainted with the patterns of Catholic ecclesiastical careers, there was nothing exceptional in the early years of Oscar Romero: born in 1917, worked as a carpenter’s apprentice, entered the seminary, was ordained a priest, studied in Rome, appointed rector of the national seminary, secretary of the bishops conference, assistant bishop and then, in 1977, named archbishop of San Salvador, the capital of El Salvador.

In 1977, the population of El Salvador was highly polarized. The peasants had organized themselves and were striving to overthrow the oligarchic rule that had governed El Salvador for more than a century. The wealthy, powerful families that controlled the politics and economy of the nation had employed the army and paramilitary “death squads” to terrorize the population in order to put an end to the camposinos’ uprising. Geopolitical interests exacerbated the tensions, with the American government involved in training and supporting the Salvadoran military to counter the Marxist ideology proposed by some of the popular leaders.

At first, Romero’s consecration as archbishop of the capital city was welcomed by the ruling elites, as he had been seen as theologically and socially conservative. However, a short time after he became bishop, the murders of two priests brought about a change, or as Romero put it, an evolution in his thinking. He demanded an inquiry into the murders and set up a permanent commission for the defense of human rights. People began flocking to his Masses on Sundays and his sermons were printed and distributed throughout the country. He became the voice of the oppressed people crying for their rights and dignity. His championing the cause of the people also engendered criticism against him on the part of the ruling elite and even some of his fellow bishops. He was accused of “inciting class struggle and revolution” and of being infected with Marxist ideas.

The social situation continued to deteriorate, with mutilated corpses left hanging from trees, bombs detonated in newspaper offices, churches, and government buildings, and massacres of peasants occurring on a weekly basis. In this context, to those who were trying to put down the rebellion with terror tactics, Romero spoke of the qualities of true peace. He said, “Peace is not the product of terror or fear. Peace is not the silence of cemeteries. Peace is not the silent result of violent repression. Peace is the generous, tranquil contribution of all to the good of all. Peace is dynamism. Peace is generosity. It is right and it is duty.”

Some accused Romero of meddling in politics and demanded that he confine his preaching to “spiritual” matters. Romero responded: “A church that suffers no persecution but enjoys the privileges and support of the things of the earth - beware! - is not the true church of Jesus Christ. A preaching that does not point out sin is not the preaching of the Gospel. A preaching that makes sinners feel good, so that they feel secure in their sinful state, betrays the Gospel’s call.”

Romero began to receive death threats and, as time went on, it became more and more clear that his life was in danger. However, he was not deterred by the threats and, in fact, his own preaching became sharper and more difficult for those in power to ignore. On 23 March 1980, Archbishop Romero made the following appeal to the men of the armed forces:

“Brothers, you came from our own people. You are killing your own brothers. Any human order to kill must be subordinate to the law of God, which says, ‘Thou shalt not kill’. No soldier is obliged to obey an order contrary to the law of God. No one has to obey an immoral law. It is time you obeyed your consciences rather than sinful orders. The church cannot remain silent before such an abomination. ...In the name of God, in the name of this suffering people whose cry rises to heaven more loudly each day, I implore you, I beg you, I order you: stop the repression.”The following day, Romero was shot dead while leading the congregation in worship of God.

From Oscar Romero, I learned, first of all that making peace does not mean a passive acquiescence to injustice or oppression. It does not demand that one remains silent when some are suffering at the hands of others. It does not mean that one should become a “doormat” for others to walk over or put up with wrongs and violence in order to “keep peace at any cost.”

Our religious faith does not teach passivity, but teaches us not to respond to violence in kind. Romero resolved this seeming paradox by his insistence on the truth. For him, to preach a comfortable message that did not call upon wrongdoers to confront the true nature of their violent deeds would be to preach a perversion of the Gospel. Violent situations require peacemakers speak the truth and call sin by its name. We all know how difficult this is to do, especially when the violent are people of power, prestige, and influence. We can find in Oscar Romero a martyr to the truth, one who dared to speak his faith even when he knew it would mean his death.

4. M. Fethullah Gülen: An activist who teaches peace and practices dialogue.

The final peacemaker I will speak about here is Fethullah Gulen, a contemporary Turkish thinker, spiritual leader, and creative educator. Living in the next generation after Said Nursi, Gülen took up Nursi’s call for an effective dialogue between believing Muslims and believing Christians. What form should such a dialogue take? What are the priorities? How can Said Nursi’s directives to struggle together against the common enemies of ignorance, poverty and disunity be put into practice in a world which has continued to evolve in ways that are sometimes encouraging, but in other ways, quite disturbing? This is the challenge taken up by Fethullah Gulen, affectionately called “Hoca Effendi” by his associates and students. Gülen never met Said Nursi and, while he speaks highly of him and claims to have been greatly influenced by his writings, he denies being a follower of Said Nursi in any sectarian sense.

Some scholars consider the movement associated with Gülen to be one of the transformations that have occurred as Said Nursi’s thought continues to be reinterpreted and applied anew in evolving historical and geographical situations. One scholar to study the movement, Professor Hakan Yavuz, notes that “Some Turkish Nurcus, such as Yeni Asya of Mehmet Kutlular and the Fethullah Gulen community, re-imagined the movement as a ‘Turkish Islam’.” Another scholar, Dr. Ihsan Yilmaz concurs: “Nursi’s discourse ‘has already weathered major economic, political, and educational transformations’... Today, the Gulen movement is a manifestation of this phenomenon.”

Where Gülen most clearly answers the call of Said Nursi is by taking up the challenge to combat ignorance. There are now over 300 schools around the world inspired by the convictions of Mr. Gülen, set up, administered, and staffed by his circle of students and associates. The schools try to bring together educational objectives that are too often dispersed among various school systems. They seek to give a strong scientific grounding, together with character formation in non-material values, which includes cultural, ethical, religious and spiritual training. In addition to the formal education carried out in schools, Fethullah Gulen’s movement has pursued non-formal education through television and radio channels, newspapers and magazines, cultural and professional foundations.

|

| Fethullah Gulen with Ecumenical Patriarch of the Orthodox Church, Bartholomew |

Mr. Gülen’s was one of the first Muslim voices heard in condemnation of the terrorist acts committed on 11 September 2001. Within 24 hours of the tragedy, Mr. Gülen wrote an open letter in which he stated: “What lies behind certain Muslim people or institutions that misunderstand Islam getting involved in terrorist attacks that occur throughout the world should be sought not in Islam, but within those people themselves, in their misinterpretations, and in other factors. Just as Islam is not a religion of terrorism, any Muslim who correctly understands Islam cannot be thought of as a terrorist.”

Conclusion

As a Christian involved in working with Muslims and other religious believers for peace through interreligious dialogue, I am grateful for the insights of Said Nursi and for the leadership in this field provided by Fethullah Gülen. What Said Nursi and Fethullah Gülen have in common with Rosa Parks and Oscar Romero is a strong religious faith which has shaped their thinking and their commitments to stand for peace in a violent world. All four have met rejection, not because they had committed or advocated criminal activity, but because they upheld religious values and taught a non-violent activism. Together with many other peacemakers too numerous to mention, they have shown, in the words of the recent World Social Forum, that “another world is possible.”

Bibliography

Rosa Parks

- Rosa Parks, Quiet Strength, Zondervan, 1994.

- Grace Lee Boggs, Rosa Parks, Penguin Books, 1990.

- Rita Dove, On the Bus with Rosa Parks, Norton, 1999.

- Beatrice Seagel, The Year They Walked: Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Simon & Schuster, 1992.

- Rosa Parks and Jim Haskins. Rosa Parks: My Story, Dial, 1992.

- Kai Friese, Rosa Parks: The Movement Organizes, Burdett, 1990.

- Said Nursi, Risale-i Nur. Most of this immense Qur’an commentary has been translated into English by _ükran Vahide and published as separate volumes (“The Words,” “The Letters,” “The Flashes,” “The Rays,” “The Damascus Sermon”). Perhaps the most approachable version is that on CD-ROM, “The Risale-i Nur collection.

- Şükran Vahide, Bediuzzaman Said Nursi, Izmir: Sözler Publications, 1992.

- Sherif Mardin, Religion and Social Change in Modern Turkey: the Case of Bediüzzaman Said Nursi, New York: SUNY Press, 1989.

- Camilla Trud Nereid, In the Light of Said Nursi: Turkish Nationalism and the Religious Alternative, Bergen: 1997.

- Hamid Algar, “Said Nursi and the Risale-i Nur”, Islamic Perspectives Studies in Honour of Sayyid Abu’l-A'la Mawdudi, Khurshid Ahmad and Zafar Ishaq Ansari eds., Leicester: The Islamic Foundation, 1979, pp. 313-333.

Oscar Romero

- Carmen Chacon, Salvador Carranza, Juan Macho, Inocencio Alas, Carmen Elena Hernandez, Maria Isabel Figueroa, Jorge Lara‑Braud, “The Reluctant Conversion of Oscar Romero

- Memories of the Archbishop on the 20th Anniversary of his Assassination,” Sojourners, March‑April 2000.

- Anna L. Peterson. Martyrdom and the Politics of Religion: Progressive Catholicism in El Salvador’s Civil War, SUNY Press, 1997.

- Oscar A. Romero. The Voice of the Voiceless: The Four Pastoral Letters and Other Statements, Introductions, commentaries and selection of texts by R. Cardenal, I. Martín-Baró and J. Sobrino. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 1985.

- James R. Brockman. Romero: A Life., Maryknoll: Orbis, 1989.

- Oscar Arnulfo Romero. The Church is All of You: Thoughts of Archbishop Oscar Romero. Compiled and trans. by James R. Brockman, S.J., Minneapolis: Winston Press, 1984.

Fethullah Gülen

- M. Fethullah Gülen, Essays, Perspectives, Opinions, Rutherford N.J.: The Light, 2002.

- M. Fethullah Gülen, Key Concepts in the Practice of Sufism, Fairfax, Va.: Fountain, 1999.

- Lynne Emily Webb, Fethulah Gülen: Is There More to Him Than Meets the Eye? Patterson, N.J., Zinnur, n.d.

- M. Hakan Yavuz and John L. Esposito, eds., Turkish Islam and the Secular State: the Gülen Movement, Syracuse: Syracuse U.P., 2003.

- Ali Ünal and Alphonse Williams, Fethullah Gülen, Advocate of Dialogue, Fairfax: Fountain, 2000.

Related Articles: